History of the Field

Conventionally, electronic literature has been characterized as falling into four general periods: the so-called Archaic period, meticulously documented and researched in Chris Funkhouser’s Prehistoric Digital Poetry: An Archeology of Forms, 1959-1995 (University of Alabama Press, 2007). Overlapping with this is the period from 1980-95 dominated by stand-alone narrative hypertexts, many of them published by Eastgate Systems. Although many will no longer play on contemporary operating systems, some have been updated, particularly Michael Joyce’s Afternoon and Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl. The period from 1995-2015 is dominated by web works displayed on tablets and computer screens; an authoritative source here is Scott Rettberg’s Electronic Literature (Polity Press, 2017), noteworthy for its encyclopedic survey of electronic literary forms, its contextualization of electronic literature with earlier experimental literature, and its attention to the specificities of the technologies utilized by the works. The so-called “third generation” of electronic literature consists of works written for cell phones; a central reference here is Leonardo Flores’s lecture on the topic.

Unlike print literature, electronic literature is dependent on technological platforms that can quickly become obsolete, making archiving the field’s history particularly challenging. Dene Grigar and Stuart Moulthrop have made critical contributions in rescuing this history through their Rebooting Electronic Literature series, showing pre-web works played on the original equipment they were designed for. They anticipate releasing a volume each year. Already available are Volume 1, with Volume 2 to be released in December 2019 Their book Traversals: The Use of Preservation for Early Electronic Writing (MIT Press, 2017) offers commentaries, criticism and descriptions of early works, and their video series shows key works being played through (since hypertext works offer multiple pathways, the idea of a “traversal” offers one possible pathway through a work). Moreover, their Pathfinders project features interviews with many of these early writers. More on Pathfinders here.

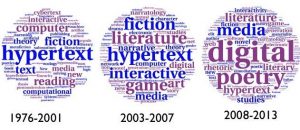

The changing shape of the field is illustrated in these word clouds from Jill Walker Rettberg. The database for the images were the tags for dissertations on electronic literature.

The size of each word represents how often that term appears in the database. The images show “hypertext” is clearly dominant in the early period from 1976-2001. By 2003-2007, “ hypertext” is still important but now has a number of close competitors, including “games,” “interactive,” and “fiction,” with “art” on the rise. By 2008-2013, hypertext has shrunk considerably, now overshadowed by “digital,” “poetry,” and “media.” This shows the growing overlap between media studies and electronic literature, and perhaps also a realization that long-form narratives are difficult to realize successfully in electronic media, whereas poetry is well suited to shorter text lengths, smaller screens, and a wide variety of interfaces.

Locating and Choosing Primary Works

The ELO has published three curated collections of electronic works (2006, 2011, 2016), chosen in competitions and juried by experts in the field.

Collectively, these offer a plethora of high-quality, important works spanning several genres and making use of many different software affordances. As the collections progressed, efforts were made to include more works in languages other than English and from regions other than North America. Various filters allow users to select specific groupings of texts. For example, in Volume 1 clicking on “keywords” brings up such groupings as authors from outside North America, works employing animation, documentaries, databases, procedural works, games, and women authors. These filters make it easy to choose works appropriate to specific topics in a course or to create a course around one form or orientation, for example games and electronic literature. Since there are far more works collected here than can be used in any one course, in my experience a useful strategy is to combine assignments where the class all reads the same work with others in which each student to asked to select one of their choice, explore it thoroughly, and present on it to the class. This enables a wider spectrum of works to be discussed, without losing the focus that sustained close reading enables. Also in my experience, students may need instruction about what close reading entails in digital contexts, specifically how to integrate attention to different modalities and traditions such as verbal cues, sounds, motions, gestures and code, for example. Since electronic media are often associated with skimming and scanning rather than sustained attention, they may also need encouragement to read slowly and with deep attention to the work’s complexities.

In addition to the ELO Collections, there are other databases and collections that can be consulted. One of the most comprehensive is the Electronic Literature as a Model of Creative and Innovation in Practice (ELMCIP), with a focus on European works. The Electronic Poetry Center at the University of Buffalo also features works of poetry. I ♥ E-Poetry also has a fine database of electronic poetry. It is easy to feel overwhelmed with all these riches, however, so curated collections are better choices when first learning the contours of the field.